I received some super valuable, critical feedback from one of our best clients last week.

“It would really help if you answer questions more simply – you’ve earned our trust to handle the rest. Trust us to ask for details when we need them.”

When I had a moment, I took a look back at my Slack and Asana threads, I glanced at a few minutes from a recorded Zoom. There it is. Many simple questions with long, detailed responses written as if I was asked for every background detail that they MIGHT SOMEDAY ask.

The Curse of Knowledge

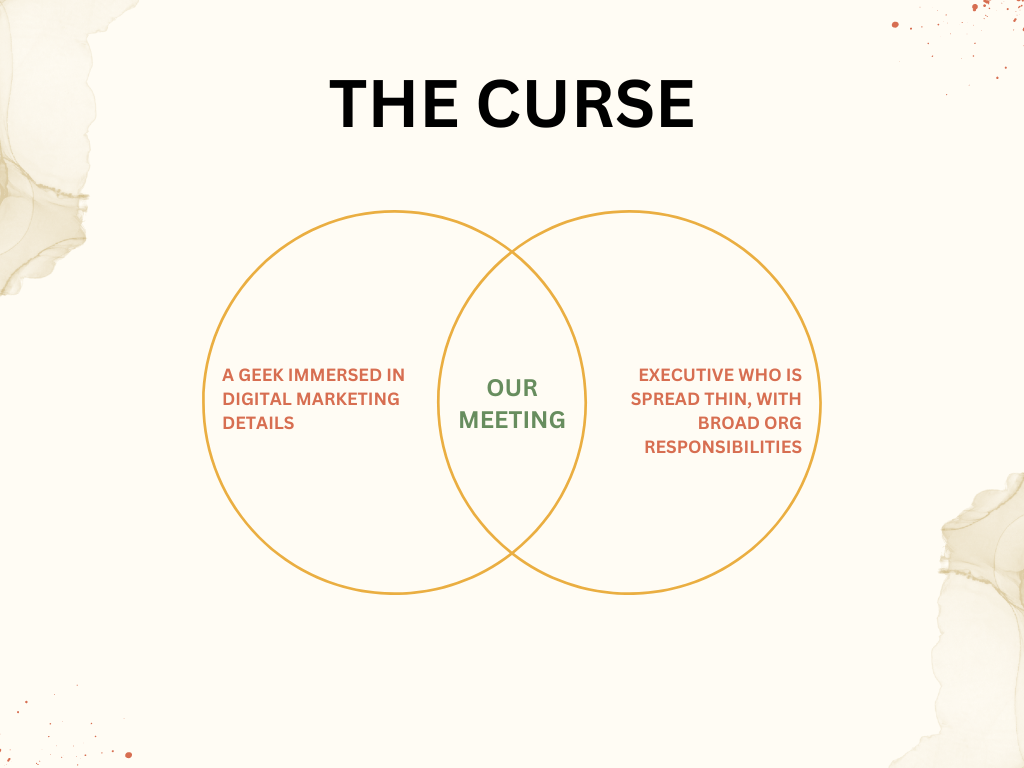

Reflecting on this…I encountered this concept which resonated. “The Curse of Knowledge” – While my clients are often skilled marketers, salespeople, executives or even CEOs, we do not have a perfect shared understanding of each others’ domains.

This illustrates things nicely

In subsequent days I made a list of possible reasons

- Impression Management – I want to showcase knowledge and ability in every brief interaction. I don’t get to collaborate with my clients 1:1 as much as I’d like, so I cram a lot into each meeting. This leads to rushed answers and then a compulsion to revise and revise. The end result in noise.

- Overcompensation/Security – Exhaustive answers to cover all angles and ensure that I’m adding enough value to the conversation. This is a fear-oriented response and is also part of the extremely common impostor syndrome behavior among senior consultants.

- Lack of Non Verbal Queues: With a consulting relationship, and in the absence of non-verbal cues that come with Zoom meetings these days, it’s easy to accidentally tell oneself that they are failing to communicate something well mid-stream and to overreact to that.

- Fear of Oversimplification – Simpler answers are harder to generate, and in some cases, have downstream implications if details aren’t included. While this is harder to overcome in verbal conversation, in other, more asynchronous forms, a pause and thoughtfulness might lead to a simpler answer.

- The Curse of Knowledge – I’m immersed in digital marketing every workday, and therefore there’s a risk that I lose touch with the higher-level needs of someone for whom digital marketing is part, but not all of their day. Immersion becomes a barrier, not an enabler.

I took a shot at some Ideas to try during the workday:

- For tools like Slack, Asana, and Monday: I now write my messages in a notepad first, revising them and taking a 10-15 minute break before finalizing and pasting them in. This step away from the platform gives me a moment to empathize with the listener’s situation. Imagine their busy day and multiplicity of responsibilities. Imagine that the digital marketing meeting we’re having is one of many meetings that day, and that they may be tired, distracted or dealing with some difficult issues professionally or personally.

- For emails: I send the draft to myself first to experience the message as a recipient would, opening and skimming it to gauge how it reads with fresh eyes. What if I read it on my phone in a fleeting moment between meetings. What if someone interrupted me half way through?

- For online meetings: Mindfulness applies here, but I’m hopeful that AI speech to text will advance soon so that I can get real-time feedback as I participate in Zoom, Teams and Webex calls. Our PBX has such recognition which will put a message on screen with suggestions, such as “monologue, take a break” but this doesn’t help in Zoom, and it’s quite primitive.

- In person: Mindfulness practices. Assess how I feel about the meeting – how I feel in my body. Explore intention – to deliver understanding and take-aways that are useful with minimal noise. If excited or nervous, think back about how these feelings affected previous conversations and pre-adjust. Set mental limits on the length of the answer – some suggest covertly tapping once per word you speak with a finger. Consider mindful listening and brevity in active listening responses so that I am ever aware of balance.

By applying these methods, perhaps you can make your communication clearer and more accessible, reducing the risk that your expertise becomes a barrier to understanding.